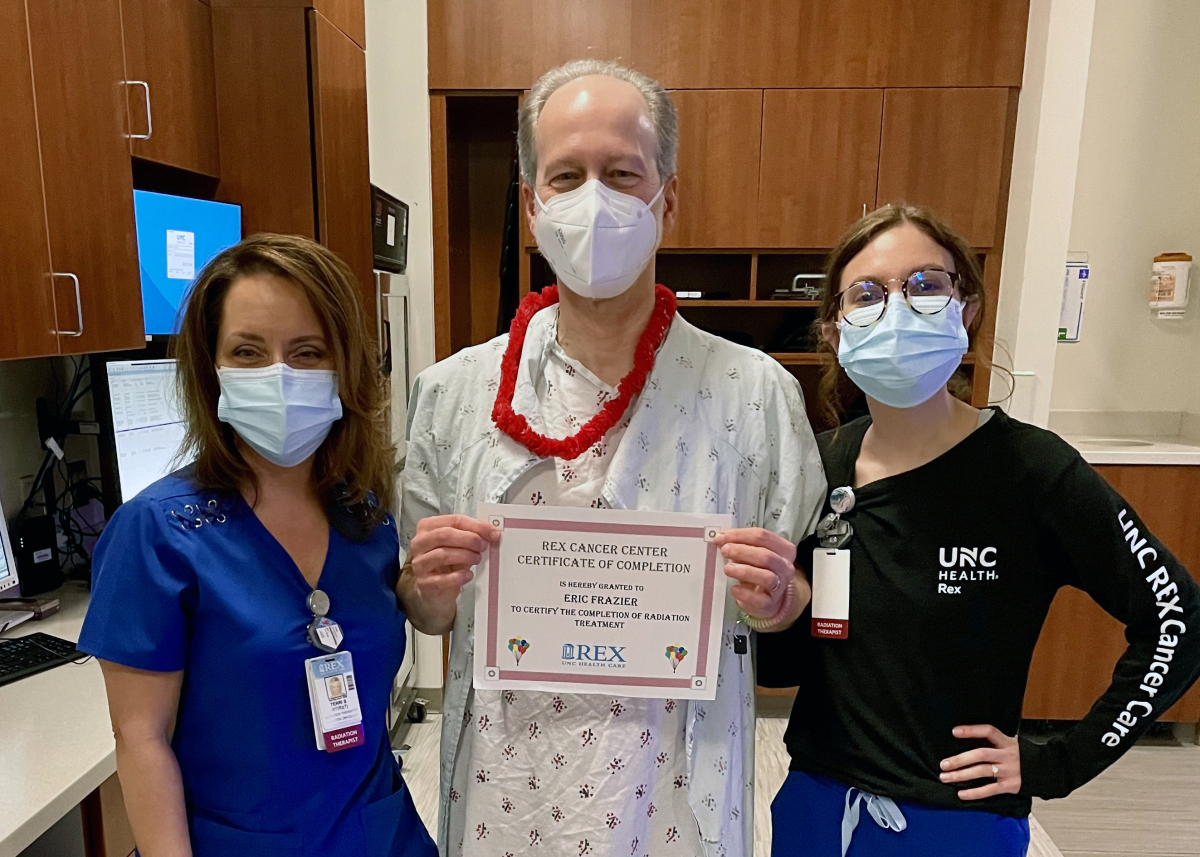

Before my third anniversary being cancer-free after treatment for a rare neck cancer, I was diagnosed with prostate cancer. That was one year ago, and there’s no way to sugar-coat it: Fighting two different cancers in four years sucks.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not here to complain or seek sympathy. I have twice been the beneficiary of early detection of treatable cancers. Meanwhile, last year I lost a longtime friend only weeks after he shared his diagnosis. During treatments, I saw cancer patients in such dire shape it brought me to tears. I’m one of the lucky ones.

With that good fortune, I feel obligated to share whatever insights might help others. These musings expand on “Cancer Lessons: What It Stole and Why I’m Still Grateful,” penned after my first illness. I don’t plan to write further about my cancers (and hopefully won’t have more diagnoses), but if time changes my perspective, I might revisit this topic. For now, here’s what I’ve learned.

Accept life’s messy timing

I completed 30 radiation treatments in November 2019 (following surgery to remove my right submandibular salivary gland that September). As I regained strength to socialize and travel again—the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Shutdowns. Quarantines. Widespread hysteria. Social unrest.

At least I was healthy. And since I’ve worked from home since 2009, staying home was no challenge. The wait for vaccines meant more time watching our toddler granddaughter—a joyful distraction from the madness.

I breezed through my two-year cancer follow-up. No evidence of disease. Few lingering side-effects. Then came my annual physical and lab work. My PSA (prostate specific antigen) score, which had zigzagged higher over the years, crossed the recommended level for my age.

My primary doctor referred me to a urologist, who performed a biopsy, which confirmed prostate cancer. No! Not now! Why me? Such thoughts are as useless as complaining about the weather. I turned my time and energy to learning about another disease.

Get a second (and maybe a third) opinion

When my biopsy results came back, the urologist declared flatly that my only option was surgery to remove it—a radical prostatectomy (RP). My reading and consultations with others, including my former urologist in a different town, suggested otherwise.

I needed further testing to determine whether radiation and hormone-blocking therapy could kill the tumor while sparing me the loss of function that RP often causes. My research expanded from reading clinical studies to surveying providers and facilities near me.

Ultimately, I got two new doctors (urologist and oncologist), an MRI, an MRI-guided second biopsy, and an OK to proceed without removing the gland. I’m glad I did my homework and found doctors who inspired my trust.

Don’t fight the last illness

With a second diagnosis, it was easy to slip mentally into “fighting the last war.” I’d been there before, so I thought I knew what to expect. Wrong.

Obviously, neck and prostate cancers occur at opposite ends of your body. But mine were both solid tumors inside glands and had eerily similar names: adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) and prostatic adenocarcinoma.

However, science has found no link, and their occurrence differs drastically. Only 1,300 people (60% women) in the United States are diagnosed annually with ACC, while more than 288,000 new prostate cancers are expected to be diagnosed this year among U.S. men.

My neck surgery incision required weeks to heal, but radiation needed to start as soon as possible to kill any stray cancer cells left behind. The tight window hijacked my calendar.

Head and neck radiation sounds unpleasant and was. Treatment required having my head clamped down immovably for about four minutes—30 times. By the third session I acclimated and could relax throughout. The rays caused some temporary facial hair loss and burned part of my neck deep red (Insert joke). It healed quickly but remains smooth as a baby’s bottom, permanently hairless.

My prostate diagnosis confirmed that I needed radiation, but the timing was flexible. My wife and I used the opportunity to move up a planned anniversary trip ahead of treatment.

A month before radiation, my urologist used a special ultrasound-guided needle (I was under general anesthesia) to insert tiny gold beads into my prostate and a slowly dissolving hydrogel behind it. The beads glowed on CT scans, creating targets for the radiation techs. The gel kept the rays from causing bowel problems.

Prostate radiation left no visible marks beyond three tiny tattoos used to align me. A custom leg mold kept me still. However, relaxing throughout was impossible because keeping my prostate in the bullseye required having my bladder 95% full. Every day on my 20-minute drive to treatment, I had to drink 22 ounces of water. When my turn on the machine arrived on time, everything went fine. When appointments fell behind, my discomfort grew from foot-shaking to fist-clenching to running to the toilet and starting over. By my 28th and final session, Mr. Irradiated Bladder did not want anything to do with water.

Finally, while I experienced fatigue throughout both treatments, the prostate radiation made my abdomen tender and exercise difficult. Meanwhile, the hormone blocker increased my appetite and lowered my energy. You’ve seen the TV commercials hawking pills for low-T? Try no-T.

Express your gratitude

During my neck radiation, I experienced odd moments of euphoria afterward that I attribute to the rays passing through my brain. My drives home felt wonderful. I focused on the autumn leaves turning golden. The dappled sunshine flickering though them. That crunch of leaves underfoot, and how brisk air tickles your lungs when you step outside.

Amid the fatigue, the eating challenges and grind of daily trips to the cancer center, I learned to zoom in on the good stuff, automatically shrinking the bad stuff and sometimes pushing it out of view. I committed to identifying and being grateful for at least one good thing every day. I kept up this practice for a long time, but eventually the “daily” part began to slip.

My January drives home from prostate radiation (down the same road, still beautiful) seemed prosaic. No heady splendor. I was just glad to get home before my bladder burst. But when people questioned me about my illness, I found that my gratitude radar was still there, waiting to be called upon.

Verbalizing this or that thing I felt thankful for was as easy as ever. I realized that gratitude should be expressed before the thought dissolves in the ferment of daily busy-ness. So, when you’re feeling grateful, tell somebody or write it down. (BTW, thanks for reading!)

Make time every day for who and what you love

Often throughout this essay I’ve used the word “my” when the correct word should be “our.” Nobody fights cancer alone, and my cancers profoundly affected my wife, Margie. I could cite her every day as the object of my gratitude as easily as being grateful every day for air.

Whoever cares for you, whoever tolerates you at your worst, whoever listens as you babble about symptoms and side effects and survival rates becomes as elemental to you as air, food and water. Serious illness can refine relationships to their essence.

After a double dose of being reminded that nobody is guaranteed a tomorrow, I’ve stopped being the kid who turns down one marshmallow now to get two marshmallows later. I want to feast on my daily bread today, to stop and smell the roses (and photograph them) as they bloom, to spend my time with the folks who will be there at the end—whenever that may be.

Deferred gratification is a reliable way to learn discipline. But I think I’ve outgrown it.

Screen, baby, screen!

I now get checked for recurrence every six months for ACC and every three months for prostate cancer. That’s a lot of screening, but I’m happy to be surveilled so closely. Beyond catching a recurrence, all that face time with nurse practitioners makes it less likely a new illness will sneak up on me. These follow-up intervals are the standard of care for survivors of these cancers.

For the healthy, some worry about too much testing. Health professionals debate when to start routine mammograms, PSA blood draws and colonoscopies. Critics see unnecessary expense and avoidable pain and worry when false positives lead to negative, and therefore unneeded, biopsies. I get that, but I always prefer more information to less. My many years of PSA tests showed me a trajectory that a single high score could not.

I recommend getting all the screenings and tests that your insurance covers and your providers recommend. Men, consider this passage from the American Cancer Society:

“The number of prostate cancers diagnosed each year declined sharply from 2007 to 2014, coinciding with fewer men being screened because of changes in screening recommendations. Since 2014, however, the incidence rate has increased by 3% per year overall and by about 5% per year for advanced-stage prostate cancer.”

You don’t want to find out you’ve got prostate cancer when you’re older and sicker if you can avoid it. Prostate cancer strikes one in eight men and kills one in 41, second only to lung cancer. You can prevent the worst outcome, but only if you know you have it and get treated.

Class dismissed.