The Federal Reserve is cutting interest rates again. Cheaper money is supposed to help the economy, but for savers, conservative investors and retirees the message is: “Your money’s no good here.”

The phrase has historically meant one of two things. It’s commonly a slang expression when someone else is picking up the tab. As in, “Put away your wallet. Your money’s no good here.” The payer may be showing off or laying the groundwork for a reciprocal favor. However, the phrase originated with denial of service, as in, “Even if you can pay, we don’t serve your kind.”

Fortunately, laws governing civil rights and public accommodations have rendered the original usage archaic. Unfortunately, the phrase finds a new discriminatory context as technology and economic policies increasingly favor those with lots of money and disadvantage those of modest means.

Modern financial wizards have created new ways to make your money no good, or if not worthless, at least worth less and less useful.

Credit/debits cards and other electronic payments are nearly universal. Online commerce has conditioned consumers to quick, cashless transactions. Increasingly, physical currency is either not accepted or too cumbersome to use when paying in person.

As people abandon currency, you can now find beggars on the streets of China soliciting handouts via QR codes. Just scan and donate through your smartphone. You can be sure these poor souls do not have bank accounts. They are working for crumbs doled out by others who own the accounts. The gig economy meets Oliver Twist.

Inflation

Higher up the economic ladder, long-running, near-zero rates create a new twist on the old problem of inflation—the erosion of money’s value over time. Younger readers may wonder: why worry about inflation, since it’s been low for so long? Let’s review.

Since the invention of coins, regimes have debased them, substituting base metals for silver and gold, manipulating size, etc. This was the ancient version of “turning on the printing presses” to increase the money supply. While some inflation is normal in a growing economy, high inflation distorts economic decisions and destabilizes societies. Inflation is sometimes cited as a factor in the fall of the Roman Empire.

Inflationary expectations can fuel more inflation. Once it gets rolling, runaway or hyperinflation is hard to stop. A 2012 study compiled 56 episodes of hyperinflation going back to 1795-96, in France, where monthly inflation hit 304 percent, and prices doubled every 15.1 days. Try to imagine living in post-war Hungary in August 1945, when prices doubled every 15 hours, and the daily inflation rate hit 207 percent.

In the 1970s, low growth combined with high inflation—stagflation—bedeviled the U.S. economy. Bad policies, like wage and price controls, and oil embargoes were mostly to blame. The Federal Reserve’s primary tool for fighting inflation is the Fed Funds Rate. This benchmark sets the interest rate for overnight loans between banks and influences everything from mortgages to savings accounts. The difference between the Fed Funds Rate and the interest rate you pay to borrow or receive for savings is a profit margin for banks.

Shock Therapy and Flat-lining

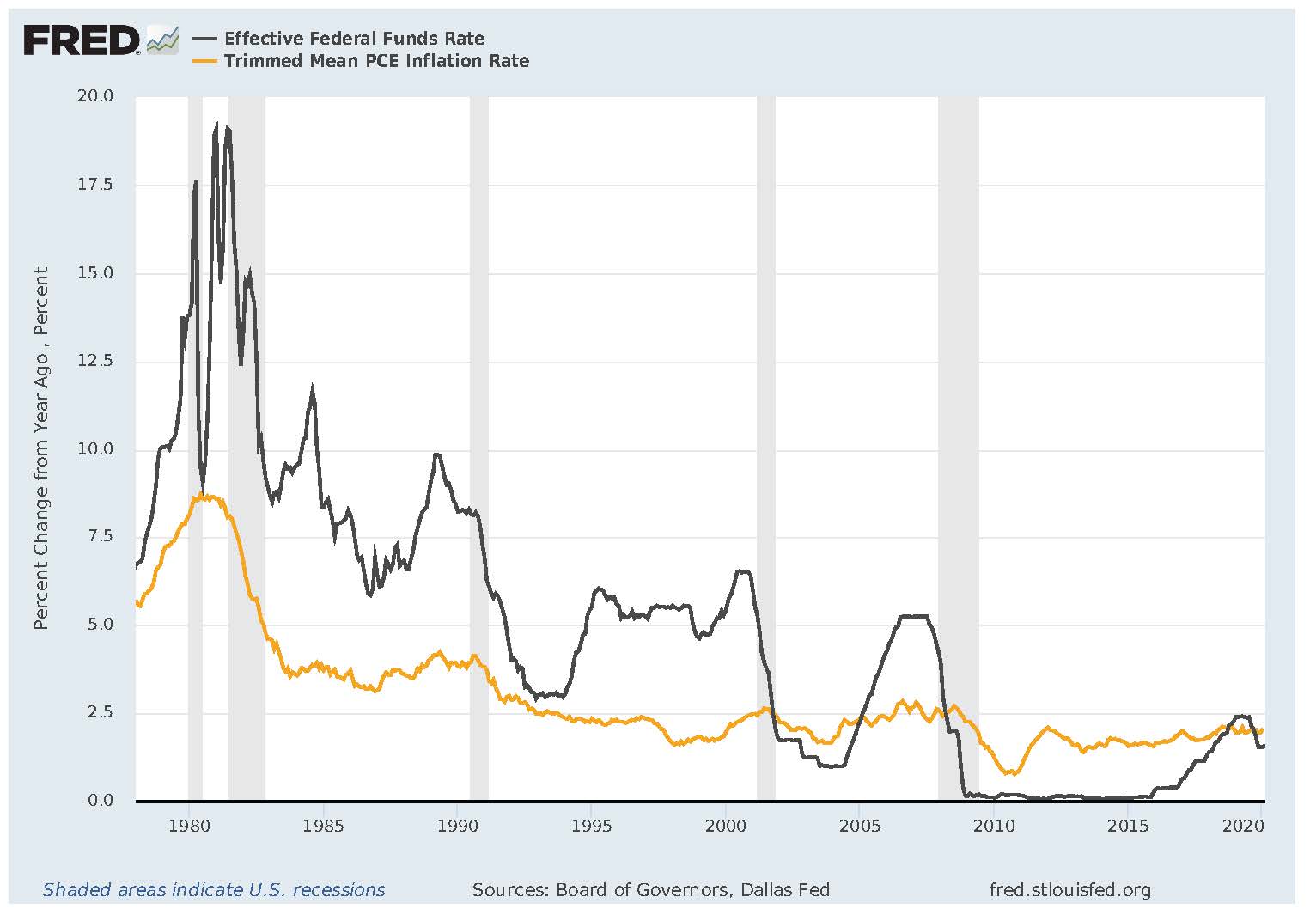

In 1981, the Federal Reserve raised the Fed Funds Rate to nearly 20 percent. As the graph below shows, this “shock therapy” is widely credited with slowing inflation from almost 10 percent to under 5 percent. It unarguably sparked a recession (shaded area).

This 1970s experience so spooked economists that the specter of inflation drove Federal Reserve policy for years. Whenever the Fed feared inflation, it raised rates. Since 1983, it’s hard to see a close correlation between the Fed Funds Rate and inflation rate. But three out of five sharp Fed rate hikes—“pumping the brakes on easy money”—closely preceded subsequent recessions.

What the graph also shows is that for most the past 40 years, the Fed Funds Rate remained at least 2-3 percentage points above the inflation rate. However, since 2001, the Fed Funds Rate has been mostly below the inflation rate. For more than half of the past decade, it was near zero.

In 2016, the Fed began trying to “normalize” rates. Given the chart, I’m not sure what rate is normal, but their intent was to get the Fed Funds Rate high enough to create room for future easing, if the economy turned down.

Fed Limbo: How Low Can You Go?

Stock speculators, and especially Donald Trump, were unhappy. People with huge piles of cash and incumbents seeking reelection like very low rates because they inflate stock prices. The wealthy can afford riskier investments to stay ahead of inflation. The Federal Reserve began to lower rates again.

The Fed Funds Rate is now 1-1.25 percent, and more rate cuts are forecast this year. In fact, more cuts are certain. As I write these words, U.S. markets have been halted by “circuit breakers”—rules designed to stall frantic trading, when indexes lose 7 percent in a session.

Savers, especially retirees, who rely on safe returns from hard-won savings are hamstrung by persistently near-zero (or potentially negative) interest rates. They are between a rock and a hard place—forced either to watch the rising costs of food, medicine and other necessities deplete their savings or to shift savings into riskier investments to keep pace with inflation—“chasing yield.”

Coronavirus has disrupted global supply chains. Professional traders are flummoxed. Bankers and economists are on defense, and national leaders (here and elsewhere) are in denial or lying. In such an environment, how can anyone who is not already quite wealthy safeguard their financial future?

The stock market has become addicted to easy money, and our nation’s leaders addicted to cheap borrowing. These addictions will eventually harm all of us. When the next recession comes, the Fed will have lost its ability to stimulate the economy through lower interest rates. And Congress will have no choice but to test how high it can pile the national debt.

Meanwhile, when you read that young people find it harder to save and older people find it harder to retire, remember what the financial titans have decreed: “Your money’s no good here.” Unless you already have lots and lots of it.